ICYMI: Start with Part 1 for an introduction to this Deep Dive series.

Please forgive the formal tone of this writing! It’s a direct serialization of an academic paper written in 2014.

The Nationalized Keffiyeh

The keffiyeh’s role as a unifying national symbol of Palestine was ascertained during the mid-twentieth century, when political developments crucially influenced its meaning, function, and consumption. Formerly, the traditional male head cloth was defined as an object of everyday attire among peasants, or fallah.1 These head cloths, usually in plain white cotton, were a practical choice for rural working men—they protected the head and neck from the sun and afforded breathability through air pockets created by folds in the fabric [Figures 4 and 5].2

Covering one’s head was an important principal in Palestinian culture: ‘The head was the locus of a man’s honor, and it was proper and dignified that it should be covered, and shameful…to leave it uncovered’.3 Although the effendi, urban men of educated middle and upper classes, did not require the same functionality from their headwear, they adhered to these societal norms by instead donning a fez, also known as a tarbush [Figures 6 and 7].

Dr. Ted Swedenburg, a prominent scholar of the keffiyeh, maintains that the keffiyeh ‘signified social inferiority (and rural backwardness), while the tarbush signaled superiority (and urbane sophistication)’, until the Palestinian revolt of 1936-1939, when these localized socioeconomic regulations of dress changed dramatically.4 The rebellion against British colonial authority was fought by peasant guerilla fighters, who ‘took on the [keffiyeh] as their insignia’.5 During the early stages of the revolt, keffiyeh provided rebels with a level of anonymity along with protection from the heat. But as fighting progressed and began to move into urban areas by the summer of 1938, the rebels’ keffiyehs became more conspicuous amongst the city-dwellers’ tarbushes and made the guerilla fighters easy targets. Recognizing their disadvantage, rebel leaders ‘commanded all Palestinian Arab townsmen to discard the tarbush and don the keffiyeh’, an order that officially intended to work as a strategic military tactic as well as a demonstration of unified resistance.6

The keffiyeh phenomenon of 1938 is typically referred to as a pivotal moment in Palestinian culture when internal differences were dismissed in favor of solidarity with the nationalist cause and in opposition of colonialism. However, Swedenburg argues that this narrative ignores the social tensions that accompanied the order.7 In reality, many effendis were reluctant to adopt the keffiyeh and were often forced to do so against their will. He suggests that Palestinian histories choose to overlook the social struggle intertwined with the national movement ‘in the interest of preserving a fiction of national unity’.8

It was this ‘fiction’ that prompted rebels to once again take the keffiyeh as their insignia when the nationalist movement was reignited in the 1960s. The keffiyeh evoked memories of a significant moment in the national consciousness when Palestinians of all social strata united in favor of a greater cause. As Palestinians’ collective identity and right to the land continued to be increasingly threatened, they ‘[clung] all the more fiercely to those symbols of rootedness’, like the headdress, which conveyed ideas of ‘cultural and historical continuity and authenticity’.9

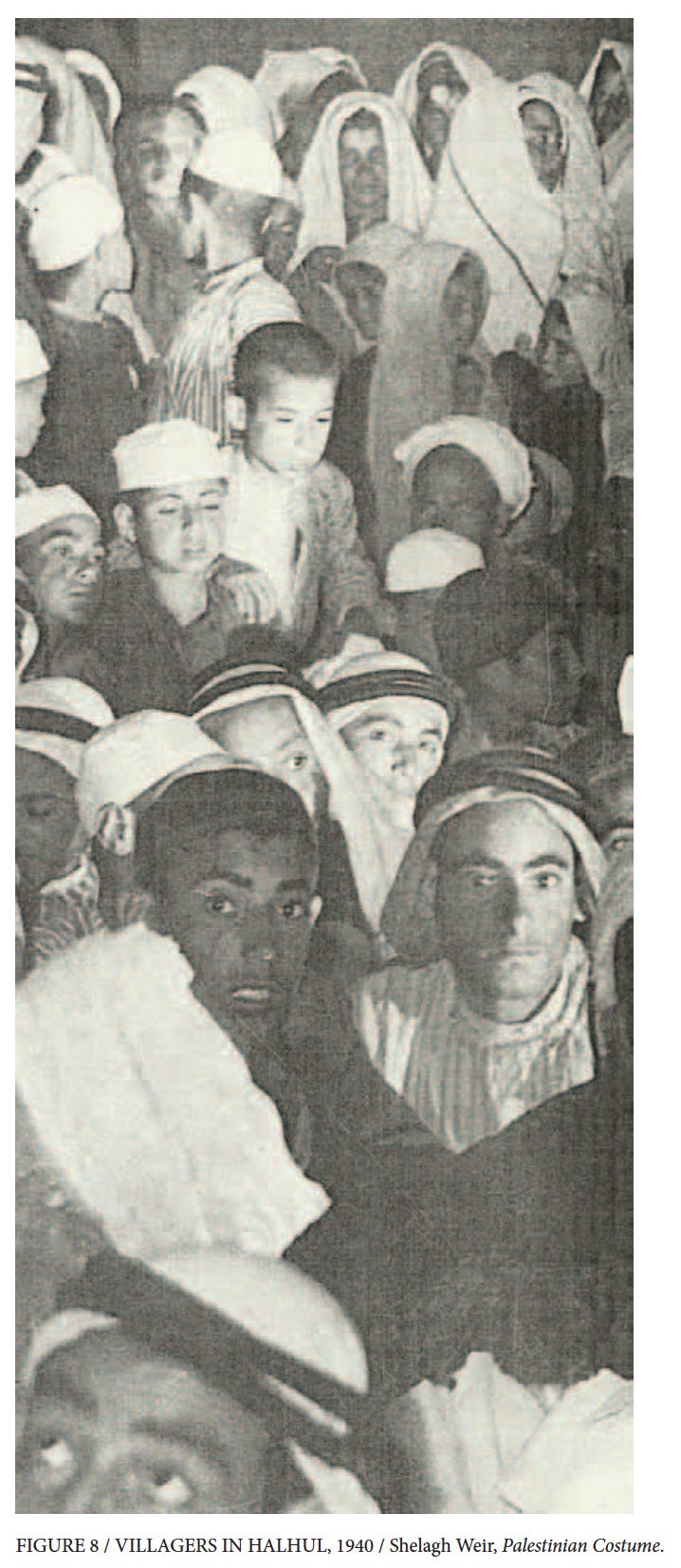

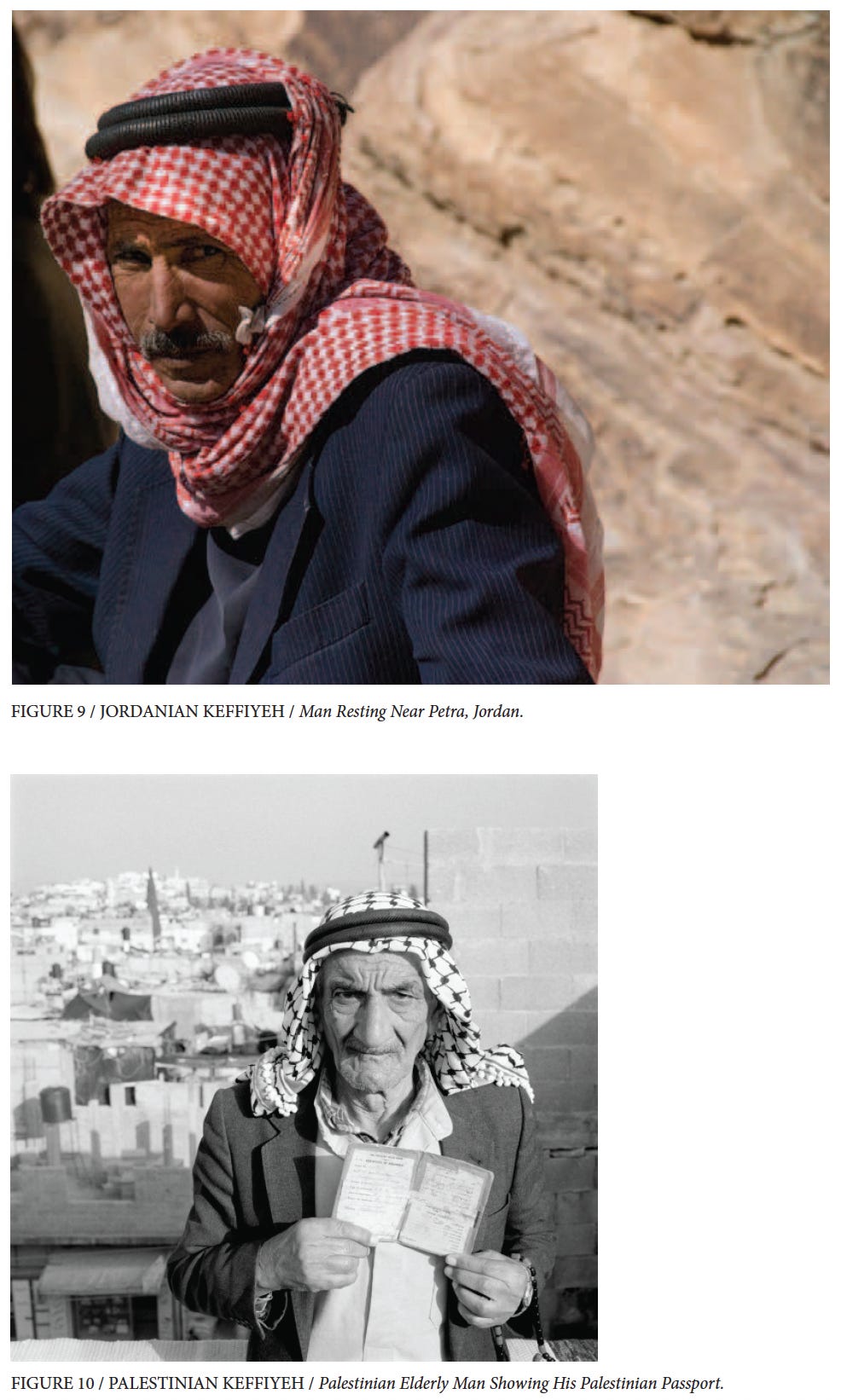

However, the revival of the headdress involved the black-and-white checkered keffiyeh rather than the plain white head cloth that had been commonly worn by guerilla fighters in the 1930s [Figure 8]. Additional evidence regarding this key transition has been difficult to locate, with many texts glossing over the change in sweeping statements: ‘Photographs show that the head cloth [in the late 1930s] was white, but later black and white checked patterns became popular’.10 According to Swedenburg’s ethnographical research, the introduction of the black-and-white keffiyeh dates to the 1950s. The British commander of the Jordanian military, Glubb Pasha, differentiated his soldiers from one another by assigning red-and-white head cloths to the Jordanians and black-and-white head cloths to the Palestinians [Figures 9 and 10].11 This observation aligns with contemporary sources’ demarcation of the two colors. The black and white coloring helped distinguish the Palestinian keffiyeh as unique amongst the plain white and other color variations that were worn elsewhere throughout the Arab world, thus adding to its value and ensuring its persistence as a national symbol.

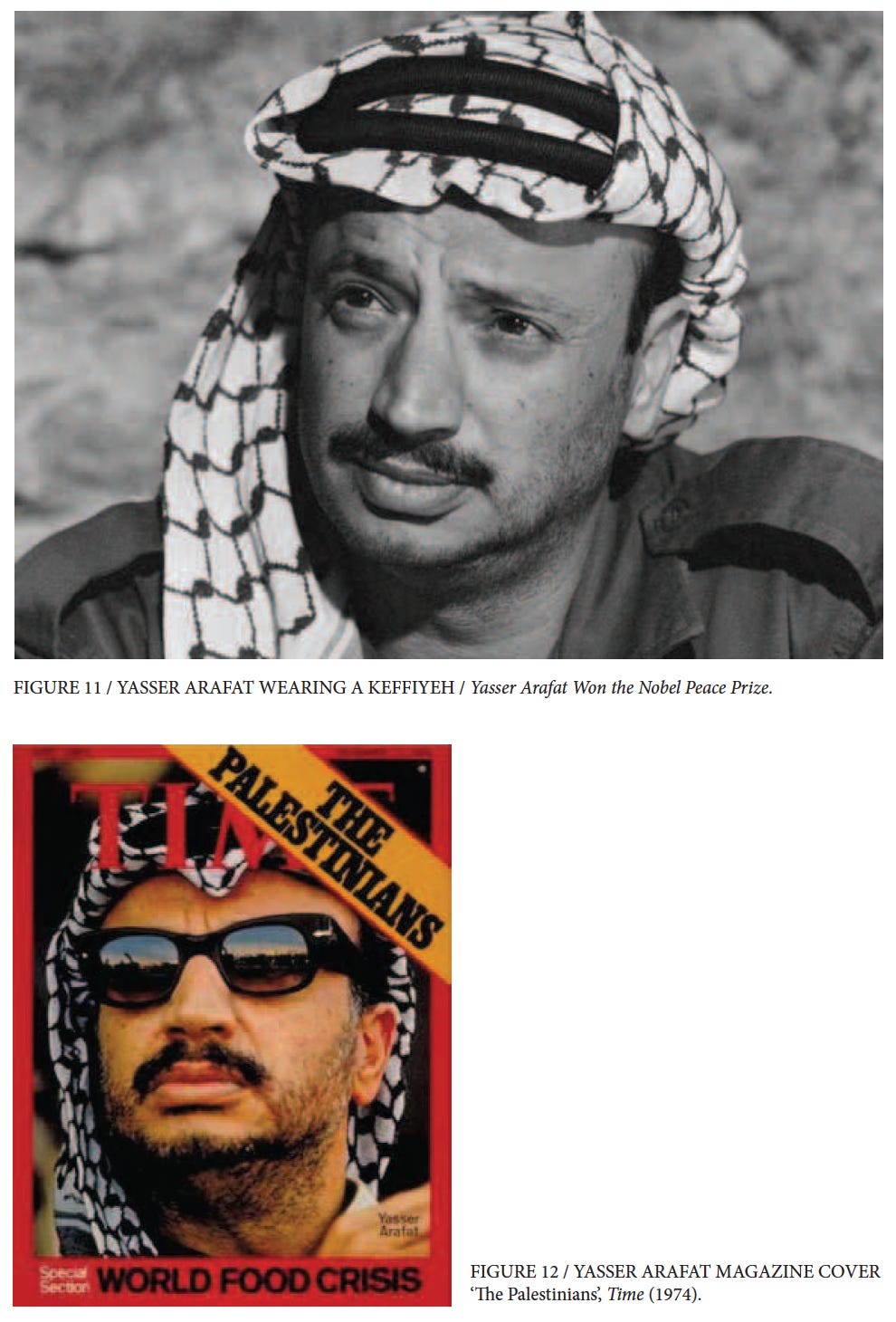

In the early 1960s, Yasser Arafat cemented the black-and-white checkered keffiyeh’s emblematic association with Palestine when he embraced the headdress as a permanent aspect of his appearance as a public figure [Figure 11]. Never photographed without it, Arafat portrayed the keffiyeh as an inherent part of his identity as a Palestinian.

Adorned in his elaborately arranged [keffiyeh], PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat invests himself with the trappings of the people-nation-peasantry, making himself simultaneously one of the people while asserting his position as their natural representative. On Arafat’s head, the [keffiyeh] dissimulates differences between the leadership and the people, between rich and poor, and unites them all in horizontal comradeship.12

By the mid 1960s, the nationalist association of the headdress had become definitively ingrained in broader Palestinian society, and its potency as a national symbol was only strengthened after the devastating Six Days War of June 1967 [Figure 12]. The subsequent Israeli occupation prompted young Palestinian men to adopt the black-and-white keffiyeh ‘as a statement of their aspirations and allegiance’.13 By 1967, the Palestinian independence movement had effectively co-opted the traditional headdress of rural peasants as the primary visual signifier of nationalist sympathies worn by leaders, rebels, and the general public alike.

The historical pedigree of the keffiyeh fulfilled a desire for authenticity and validation of Palestinian heritage that could ‘confront the drastic ruptures and fragmentation […] caused by colonialism’.14 Its symbolic power intensified in response to the repressive forces of occupation, which denied the people ‘any legitimate relation to a nation and territory called Palestine’.15 Constraints on national expression, such as the banning of the Palestinian flag between 1967 and 1903, caused those few existing symbols, like the headdress, to be ‘cathected with passionate national feeling’.16 Recognizing how the keffiyeh became a symbol of Palestinian identity and the scarcity of other portrayals of national pride is essential to understanding the sociopolitical implications of the keffiyeh’s transnational evolution between 1967 and 2007.

Next: The Globalized Keffiyeh

Note: Full bibliography (including image sources) available here

Yedida Kalfon Stillman, Arab Dress from the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times: A Short History, ed. by Norman A. Stillman, Themes in Islamic Studies (Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2000), p. 171.

Heather Coyler Ross, The Art of Arabian Costume (Fribourg, Switzerland: Arabesque Commercial SA, 1981), p. 39.

Shelagh Weir, Palestinian Costume (London: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1989), p. 58.

Ted Swedenburg, Memories of Revolt: The 1936-1939 Rebellion and the Palestinian National Past (London: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), p. 32.

Swedenburg, Memories of Revolt (1995), p. 32.

Swedenburg, Memories of Revolt (1995), p. 32.

Swedenburg, Memories of Revolt (1995), p. 35.

Swedenburg, Memories of Revolt (1995), p. 35.

Ted Swedenburg, ‘Seeing Double: Palestinian/American Histories of the Kufiya’, Michigan Quarterly Review, 31 (1992), 557–77, p. 563.

Weir, Palestinian Costume, p. 68.

Swedenburg, Memories of Revolt (1995), p. 33.

Swedenburg, ‘Seeing Double: Palestinian/American Histories of the Kufiya’ (1992), p. 568.

Weir, Palestinian Costume, p. 58.

Ted Swedenburg, ‘Popular Memory and the Palestinian National Past’, in Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in Anthropology and History, ed. by Jay O’Brien and William Roseberry (Oxford: University of California Press, 1991), pp. 152–79, p. 169.

Swedenburg, ‘Seeing Double: Palestinian/American Histories of the Kufiya’ (1992), p. 562.

Swedenburg, ‘Seeing Double: Palestinian/American Histories of the Kufiya’ (1992), p. 563.