ICYMI: Start with Part 1 for an introduction to this Deep Dive series. See Part 2 here.

If you’re not interested in this particular series, you can unsubscribe from only the ‘Deep Dives’ section by following this guide (please don’t unsub from the entire newsletter lol 🥹).

Please forgive the formal tone of this writing! It’s a direct serialization of an academic paper written in 2014.

The Globalized Keffiyeh

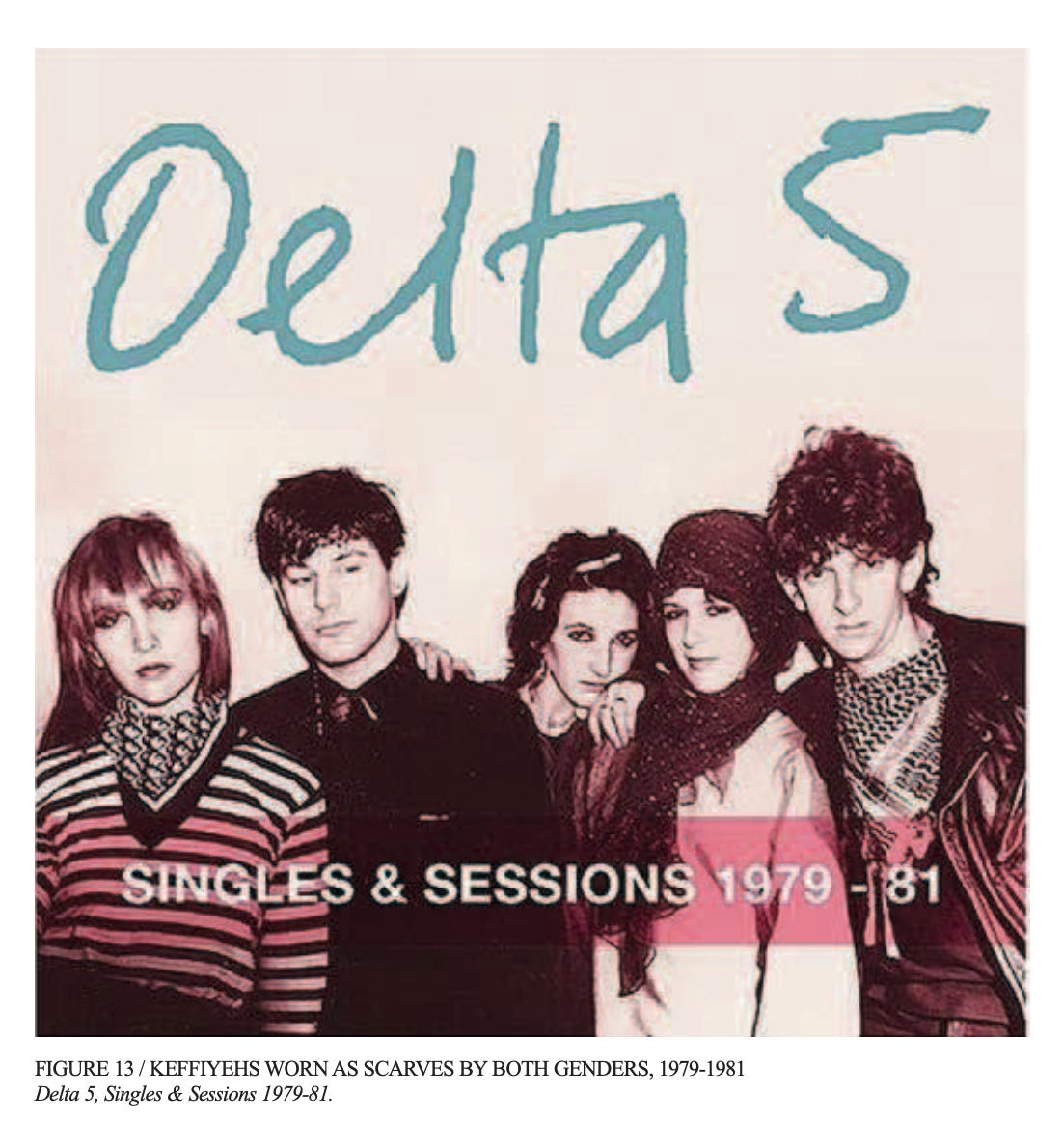

Having established the black and white headdress as a Palestinian symbol, we can consider any further developments as changes to this symbol. Its prominence among Palestinians during and immediately after the Six Days War, along with Arafat’s public adoption of the keffiyeh, instigated its acknowledgement within ‘the international language of costume’.1 Paradoxically, its increased international recognition, as a male headdress indicating Palestinian nationalist sympathies, was accompanied by many fundamental modifications in how the keffiyeh was worn and styled. By 1980, the keffiyeh was being worn by both women and men, whereas it had previously been a gendered object, and it was also being styled as a neck scarf as well as a headdress [Figure 13].

In the conventionally accepted narrative of how the keffiyeh has evolved, as recounted by the plethora of media articles written on the subject, both of these developments are dismissed as a result of Western involvement: ‘It’s newest wearers […] wrap it around the neck like a scarf’.2 Swedenburg supports this understanding of the keffiyeh’s history in his 19913, 19924, and 20105 essays on the subject, in which he tends to jump from explaining its Palestinian nationalist associations to discussing its popularity among American activists and stylish youth decades later in the 1960s and 1970s. Swedenburg describes the keffiyeh in these later Western contexts as a neck scarf worn by both young men and women.6 Throughout these essays, he only mentions the keffiyeh being worn this way by Palestinians in the late 1980s.7

By neglecting to consider the significance of these design changes to the historiography of the keffiyeh, Swedenburg inadvertently creates an incomplete narrative with limited possibilities for explaining how this transformation occurred. According to these accounts, the changes were first prompted by American activists during the 1960s and 1970s, and were then either adopted by Palestinians or independently initiated in Palestine over a decade later. In either circumstance, the agency for change is placed in the Western sphere. However, there is evidence elsewhere suggesting that these changes were not simply consequences of Western misappropriation, but were rooted in Palestine.

De-Gendering

There is evidence suggesting that the removal of gendered associations from the keffiyeh came about through Palestinian rebel efforts. Although this possibility is not mentioned in his other essays, Swedenburg alluded to it briefly in his book about the revolt of 1936-1939. In one section concerning issues of gender in Palestine at this time, he mentions a photograph from the late 1930s in which young women, in support of the nationalist cause, have replaced their usual mandil head covering with the traditionally male keffiyeh [Figure 14].8 However, Swedenburg refers to this as a unique incident that was not seen again in Palestine until the intifada of the late 1980s [Figure 15]. He seems to judge the early occurrence as insignificant, considering its absence of mention in his other writing. Yet the prospect of Palestinian involvement in the de-gendering of the keffiyeh is crucial to reconstructing its historiography through the lens of design change.

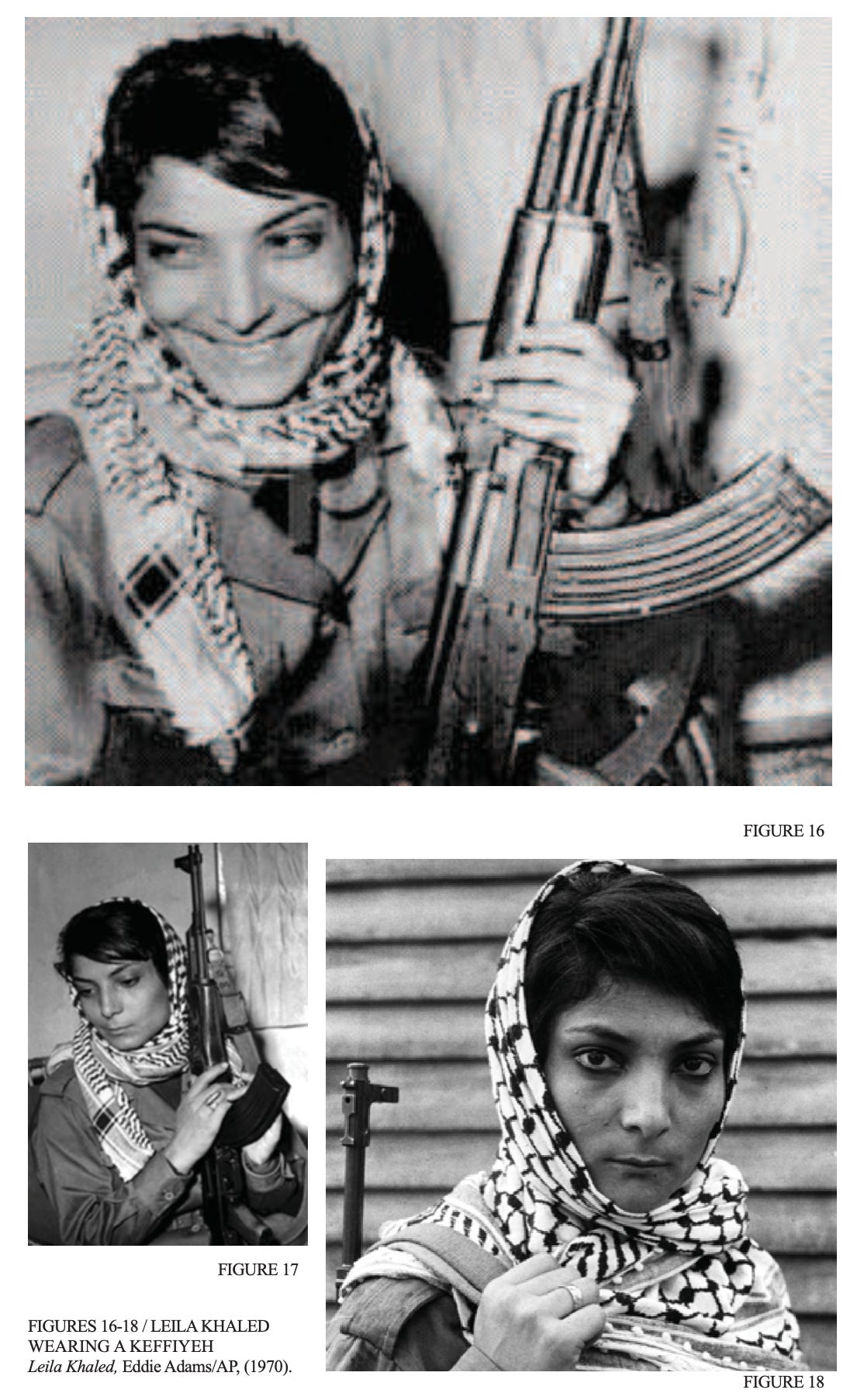

Further exploration elucidates how cross-gendered consumption of the keffiyeh was likely prompted by the rebel contingent in Palestine during the mid-twentieth century. In a thesis analyzing the keffiyeh as a cultural symbol, Nadim Damluji situates this particular change in relation to Leila Khaled’s infamous 1969 hijacking, and her ‘choice to wear and thus claim the scarf as a means to subvert her position as a woman in the resistance movement’ [Figures 16-18].9 Speaking about the state of the nationalist movement in the late 1960s, Khaled affirms, ‘women were active in the struggle […] A lot of women were coming to be trained in military camps’.10 Her commentary suggests that it was not unusual for Palestinian women to be involved with the nationalist cause. In another interview, she explains how, ‘In the beginning, all women had to prove we could be equal to men in armed struggle…So we wanted to be like men—even in our dress’.11

That Khaled prominently wore the keffiyeh in many images that were highly circulated in western media was undoubtedly a significant factor in the object’s evolution as both an international sign of Palestinian solidarity and a non-gendered object. Damluji argues that as a woman wearing the ‘masculinized’ keffiyeh, Khaled ‘challenged such imposed reductions’ and promoted a change that ‘moved the scarf away from male practicality and toward an interpretative exercise’ aligned with the Palestinian resistance.12 Her notoriety as a female terrorist is often depicted as a strong statement against patriarchy: ‘She shattered a million and one taboos overnight and she revolutionized the thinking of hundreds of angry young women around the world’.13 Regardless, Khaled was not immune to the media-led sexualization that portrayed her as a mysterious ‘girl terrorist’ and ‘deadly beauty’.14 Even respected publications like the The Guardian and the New York Times often played up her gender, with tantalizing headlines such as ‘Beauty and the Bullets’ and ‘Female Hijacker Feels “Engaged to the Revolution”’ [Figure 19].15 Given the sheer amount of publicity she received, and the keffiyeh’s prominence in published images, it is unsurprising that the scarf quickly became an internationally recognized symbol of Palestinian nationalism worn by both locals and Western activists regardless of gender.

Alternative Forms

In respect to the transformation of the keffiyeh from a headdress to a neck scarf, it is difficult to similarly locate the stimulus for change since none of the literature specifically confronts when or why this transformation might have occurred. Unlike with Khaled’s pivotal role in altering the perceived gendered classification of the keffiyeh, the change in form seems to have occurred more gradually and organically, with many contributing factors. The photographs of Khaled, for example, imply that as women began wearing the keffiyeh, they naturally adapted its form [Figures 16-18]. Instead of wearing it traditionally, as a headdress secured with an aqal, she drapes it loosely around her head and neck, in a manner similar to the Muslim hijab. This proves that there was already some variation in how the keffiyeh was worn within Palestine at least as early as 1969, and that these modifications were perhaps initiated as part of its adoption by females.

Similarly, changes in form may have been a corollary of the nationalist movement beginning to span multiple generations for the first time. As previously discussed, a keffiyeh had lost its significance as a socioeconomic indicator after the late 1930s. Because its practicality as a head covering with protection from the elements was not imperative when worn by nationalist supporters in urban areas, wearing the keffiyeh in this manner only served the purpose of sustaining tradition. Younger activists in Palestine may have simply wanted to differentiate themselves from their fathers and grandfathers by wearing the keffiyeh unconventionally. In doing so, they could simultaneously express their appreciation for the Palestinian nationalist cause while establishing their identity as a new generation of activists. This hypothesis is corroborated by a more recent account, in which a young Palestinian activist is quoted as saying that he wears his keffiyeh as a scarf rather than ‘the way old men wear it’.16 Clearly, an attitude of necessitating differentiation from previous generations exists amongst Palestinians, perhaps as a means of encouraging progress and distancing themselves from past mishaps.

Next: Alternative Forms (continued) & Globalized Consumption

Note: Full bibliography (including image sources) available here

Shelagh Weir, Palestinian Costume (London: The Trustees of the British Museum, 1989), p. 68

Kibum Kim, ‘Where Some See Fashion, Others See Politics’, New York Times (New York, 11 February 2007).

Ted Swedenburg, ‘Popular Memory and the Palestinian National Past’, in Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in Anthropology and History, ed. by Jay O’Brien and William Roseberry (Oxford: University of California Press, 1991), pp. 152–79.

Ted Swedenburg, ‘Seeing Double: Palestinian/American Histories of the Kufiya’, Michigan Quarterly Review, 31 (1992), 557–77.

Ted Swedenburg, ‘Keffiyeh: From Resistance Symbol to Retail Item’ (The Palestine Center, Washington D.C., 2010) <http://www.thejerusalemfund.org/ht/d/ContentDetails/i/10733/pid/v> [accessed 9 March 2014].

Swedenburg, ‘Keffiyeh: From Resistance Symbol to Retail Item’ (2010).

Swedenburg, ‘Seeing Double: Palestinian/American Histories of the Kufiya’ (1992), p. 568.

Ted Swedenburg, Memories of Revolt: The 1936-1939 Rebellion and the Palestinian National Past (London: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), p. 185.

Nadim N. Damluji, ‘Imperialism Reconfigured: The Cultural Interpretations of the Keffiyeh’ (Whitman College, 2010), Liberal Arts Scholarly Repository <https://dspace.lasrworks.org/handle/10349/889> [accessed 9 March 2014], p. 9.

Philip Baum, ‘Leila Khaled: In Her Own Words’, Aviation Security International, 2000.

Katharine Viner, ‘Beauty and the Bullets: What Became of Leila Khaled, the World’s Most Famous Terrorist Pin- Up?’, The Guardian (London, 26 January 2001).

Damluji, ‘Imperialism Reconfigured’, p. 9.

Eileen Macdonald as quoted by Viner.

Viner, ‘Beauty and the Bullets’.

Bernard Weinraub, ‘Woman Hijacker Feels “Engaged to the Revolution”’, New York Times (New York, 9 September 1970).

Ann Lolordo, ‘Keffiyeh Is Above Fashion, Faction Stereotype:’, The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, 12 August 1998).