CRITIQUING CURATION & PERCEPTIONS OF TASTE

+ a summer style edit

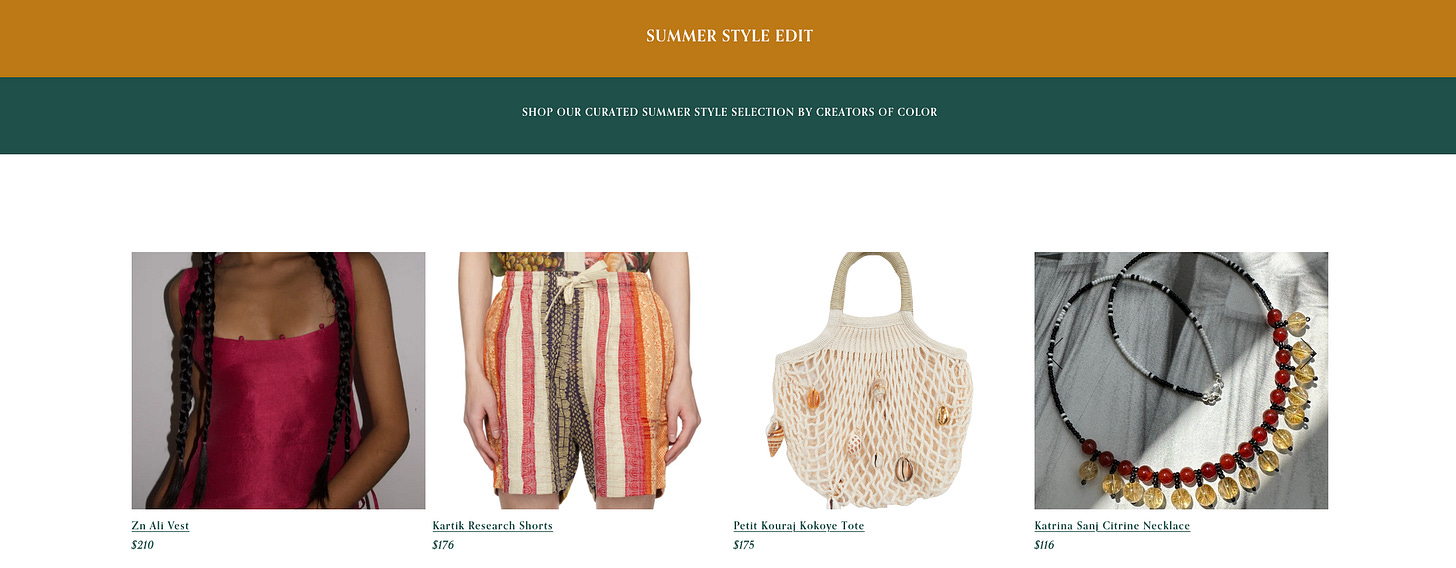

Walking around New York lately has me feeling like I’m constantly in a state of melting away. It can be difficult to get dressed when your primarily goal is wearing as little clothing as possible, so putting together this summer style edit has been both a motivational and inspirational exercise. As usual, the edit is a curation of BIPOC-owned brands, hopefully introducing you to a few that you haven’t heard of yet.

Curation has been a popular topic of discussion this year, at least in my field of work. There’s just too much stuff - to shop, to read, to watch, to listen to. And with Artificial Intelligence accelerating the algorithmic flattening of culture into an bland sea of sameness, human curation is often heralded as the solution. But if we’re going to be putting our faith in ‘curators,’ we also need to be critically aware of their associated blind spots and biases.

A few weeks ago, one of my favorite cultural strategists,

, published a piece titled ‘Beware the Curators,’ advocating for more skepticism in this regard: “Curatorial power in the hands of a privileged elite has never not been problematic.” He points out that the most popular curators “often come from similar, well-educated, high-income backgrounds,” leading them “to often overlook works by minorities or underrepresented creators.” This forces us to question whether today’s curators are really any different from the gatekeepers of the past (i.e. fashion editors); and all it takes is a look at the Substack leaderboard to realize that we haven’t made much progress - 20 of the Top 25 Fashion & Beauty newsletters are written by white women.Klein argues that the ideal solution is not following curators, but finding “the energy to explore, discover and share new works, and the self-confidence to develop independent taste.” He proposes a fundamental question: “Why on earth do we even need taste-makers and curators today?” But I’d contend that - if we intentionally choose to support those outside of our personal realms of familiarity - curators may be beneficial resources in our quest to “develop independent taste” by exposing us to new ideas we might have never encountered. Otherwise, our taste is inevitably a byproduct of our surroundings and circumstances - which, if you grew up in America, have likely been informed by an extremely Eurocentric worldview. In her essay, ‘Thoughts on Taste,’

notes how this has “tainted everything we consume monetarily, socially and culturally: the artists and authors we are told are classic, the attire we’re told is appropriate, the manners we’re taught to have — bringing into question whether you really like it or it’s just what you’ve been told you’re supposed to like to appear cultured, wealthy, and fit into a certain social class.” Challenging these ingrained markers of taste is difficult and uncomfortable.The concept of aesthetic taste was first articulated in 18th century Europe, and as Ruby Thelot recounts, functioned as a proxy measure of morality and goodness - “inversely, tastelessness was a moral affront.” The delineation between ‘good taste’ and ‘bad taste’ is inherently political and often follows colonial power structures. Throughout history, creative works originating in the Global South were regularly deemed unworthy, ostentatious, or essentially of “bad taste” - until they were recontextualized through a European lens. Examples of this are plentiful, from chinoiserie decor to wax print textiles. We continue to see similar dynamics continue to play out in contemporary culture as well. From hoop earrings to acrylic nails, many aesthetic elements beloved by Black & brown women were, for decades, ridiculed as being of “bad taste” - until they were more recently adopted in pop culture. Leading fashion tastemakers have lauded Emily Bode’s work since her brand’s inception - but why are her interpretations of traditional Indian embroideries considered more ‘tasteful,’ and thus more valuable, than the original versions?

We have been societally conditioned to perceive “good taste” in alignment with a very specific set of Eurocentric aesthetic principles. To unpack this - to attempt to extract a personal sense of style independent of what the world around us deems “good” - is a complicated endeavor. As someone who has been enamored by the worlds of beauty and fashion and design from a young age - I’ve grown to realize just how deeply I’ve internalized these preconceived principles. Hairston questions, “So, what does taste look like without an attachment to class and capital or in spite of it? What does it look like outside the lens of whiteness? Can it exist?” For me, working on these Revisionary curations began as a practice in interrogating my own perceptions of taste, growing from the hope that centering creators of color may be a starting point for decolonizing our aspirations.

Thank you for writing this! I got a lot out of it.

Thank you so much for this one, the summer style edit is gorgeous and I’m strongly considering getting a couple pieces from it :)